An informal moment at the Camp Bishop Lodge. In the center is conference co-organizer, Genko Kathy Blackman; at right, participant and NWDA board member, Koro Kaisan Miles.

Mindfulness and Release:

A Prison Dharma Conference

Plum Mountain Refuge and Northwest Dharma Association recently co-sponsored Mindfulness and Release: A Conference for Prison Dharma Workers. The weekend gathering brought together prison chaplains and volunteers, corrections administrators, consultants, and non-profit administrators, as well as former inmates, all with the aim of strengthening their ability to provide effective tools for rehabilitation and self-transformation to people in prison and to returnees (those released from prison after serving their sentence.) The ultimate goal of such efforts is to create safer, more whole communities for everyone.

The conference also attracted a few people like myself who wanted to know more about how the Dharma, mindfulness, and contemplative spiritual practices are playing a larger role in healing people inside prison and outside in our communities. The conference was an opportunity to talk at length with people who work directly in prisons and in the community, as well as with those who have been through the system. The experience certainly challenged many of my previous assumptions.

Richard Torres (l.), Oregon State Prison chaplain and Zen Buddhist, with Plum Mountain Refuge founder and conference organizer, Kobai Scott Whitney.

Working Inside

Oregon State Prison Chaplain Richard Torres began with a presentation documenting the benefit and cost-effectiveness of spiritual practice in reducing infractions in prison and recidivism upon release. Conference organizer Kobai Scott Whitney, director of Plum Mountain Refuge, then offered a sample of “Liturgy and Ritual for Prison Sanghas” while longtime prison volunteer, Rowan Conrad, led a breakout session on “Doing Retreats Inside.”

Conrad, a student of Thich Nhat Hanh and guiding teacher of the Open Way Sangha in Missoula, Montana, has been involved for twenty years as a volunteer offering meditation guidance for inmates in the Montana and Washington State prison systems. “The biggest, best thing you bring as a volunteer is you, as an authentic person, your values and beliefs. An inmate told me how astounded he was that we had come to spend the whole day meditating with him when he couldn‘t find anyone in his family to spend 30 minutes writing him a letter. So bring as many volunteers as you can from the outside to sit with the inmates when you offer retreat. Their presence will be appreciated. What are prisoners like? From my experience they are just like us, the old bell curve; a few jerks on one end, a few sane people on the other and the rest in the middle, so what works on the outside to help people to learn meditation, works on the inside.”

On Sunday, Freedom Project representatives Tuere Sala and Ruby Phillips described their use of Non-Violent Communication and mindfulness training with both male and female inmates. Based in Seattle, Freedom Project’s goal is to “strengthen our community through supporting the transformation of prisoners into peacemakers.” One key to the transformation, says Phillips, is learning how to cultivate the intention to connect.

From left to right, Carol Battistoni, Tuere Sala, and Ruby Phillips. All are prison volunteers and supporters of Freedom Project.

Returning to the Community

Some of the liveliest discussions at the conference had to do with issues facing returnees as they seek to reenter a community.

The United States has the largest prison population in the world with over 2.2 million incarcerated individuals and another 5 million on probation or parole. In 2004, 650,000 individuals were released from prison and additional 7 million were released from jails nationwide according to Doug Waddington, Superintendent, Washington Corrections Center at Shelton. From his perspective as a career corrections administrator, he sees clearly the growing problem. “The practical and emotional obstacles upon release often mean it‘s just one prison after another for many individuals. As an example: returnees are often legally denied public housing which means if their family is living in public housing they cannot live with their family when they are released. The average person doesn‘t have a sense of the insanity, the Wizard of Oz nature of the comings and goings of the system.”

Addiction is often part of the history of those leaving prison. Waddington, with fellow panel members Whitney and Carol Battistoni, a “Smart Recovery” prison volunteer, offered insight into the application of mindfulness to substance abuse and relapse for returnees in transition.

Addressing the needs of returnees and the communities they return to, Andrew McWhinnie, consultant to the Correctional Service of Canada, gave a presentation on “Circles of Support and Accountability” (CoSA), an example of a successful program of faith-based community support for released high-risk sex offenders in Canada. CoSA supports released sex offenders through development of an inner circle of community volunteers who meet with the returnee weekly. This primary group is supported by an outer circle of professional mental health, corrections, social work, and police staff. This reverses the usual approach which is to have the professionals in the inner circle in constant contact and the volunteers on the periphery. The primary goal? No more victims. Does it work? Based on several long-term studies, CoSA has resulted in a 75% reduction in re-offense rates of participants according to McWhinnie.

“What works to reduce re-offense,” says McWhinnie, “is to increase the number and quality of community ties. There is nothing more rehabilitative for someone coming out of jail than to contribute positively to the community.

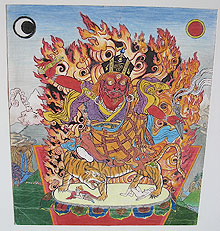

One painting from a display of Buddhist art made by prisoners. Collection of Roger Bartley.

Seeking a Sangha

“For returnees, the place you are welcomed and included to worship is in prison, but often you aren‘t welcomed when you get out.”

This was an area of much concern at the conference. Finding a community can be particularly difficult for any returnee and particularly so for sex offenders. In an afternoon panel presentation and a long evening discussion that followed, returnees among the conference participants shared from their personal experiences. One recounted how after establishing a relationship with a teacher outside, he was rejected by the sangha when he disclosed his prison history.

“It‘s too bad members of the sangha didn‘t take the opportunity to practice with their fear. Those fears will still be there,” commented Rowan Conrad. “To reject someone out of fear is contrary to what the Buddha taught.”

“Sex offenders are not the victims, we are the victimizers and have the responsibility to earn our way back. But is there a way back?” asked Roger Bartley, returnee. “I want to reconnect with community but I don't how to do that.”

Steve Heck, a longtime prison volunteer, led the evening discussion. Among the questions raised: What concerns do sangha members have about returnees? What are the true bases of these concerns? What will help members with these concerns? He hopes that continued attention to these issues will result in a guide to re-entry for returnees and receiving sanghas.

Early morning meditation by Lost Lake.

Lessons Learned

Freedom Project‘s Tuere Sala, who is also an Assistant City Attorney in the Criminal Division for the City of Seattle, described how she got interested in prison Dharma work after meeting two meditation practitioners who really impressed her with their way of being in the world and how they embodied the Dharma. She was shocked when she learned that the two of them had begun practicing in prison, where they‘d been incarcerated for a combination of more than 25 years.

“It is amazing what letting go of our own prejudices does for us. As a result of this experience and my ongoing work in prisons I have come to see that our greatest capacity to change this country will come from people who have been incarcerated. They step out into the world while going through a profound transformation and there is something about facing our failures that allows for that kind of fundamental transformation.”

One of many things that became clear for me over the course of the conference is that there is an enormous amount of work to be done to heal our communities and lessen the amount of violence. There is no perfect solution, but some things work better than others. Connection works better than isolation, recognition of our shared humanity and community works better than division into us and them, and care and attention works better than ignoring or pushing away—all lessons that may sound very familiar to practitioners of the Dharma.

As Genko Kathy Blackman, Rinzai priest and member of the Washington Department of Corrections Religious Services Advisory Committee, said in her closing talk:

“Who is going to do this work? How do we care for the who? The who is the Dharma flowing through us and the container through which it flows. It is the well of our practice that refreshes that who. All we can ever offer is our practice.”

For more information on the many programs and opportunities to get involved, check out Freedom Project at freedom-project.org or Prison Dharma Network at prisondharmanetwork.org. Information about Plum Mountain Refuge is at www.plummountain.org.

Contributor: Matthew Riggen.

Photos: Matthew Riggen, Caterina De Re.